How do destinations map the way around town for incoming tourists?

I rarely pay any attention to the tourist map I get for free at almost every hostel I stayed in, upon my arrival to a new place. Up until I came across a very wrong and confusing map that didn’t get me anywhere.

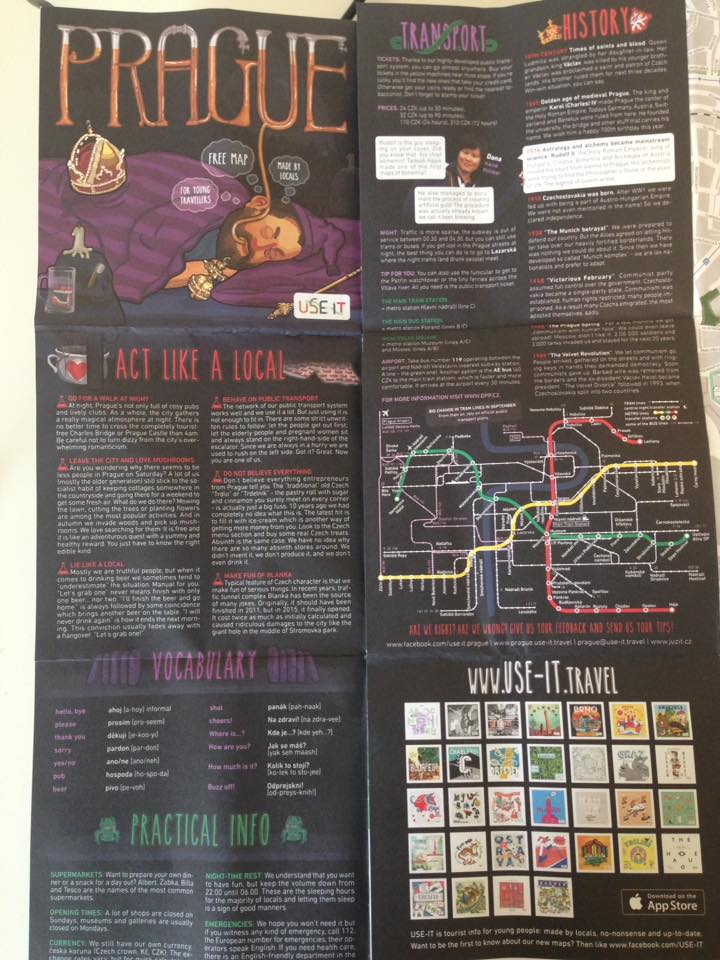

I just got back from a 5-day trip in Prague, one of the most charming historic cities in Europe. As usual, I received a free map from the hostel where I stayed. Yeap, no need to buy one from the Tourist Information centre. The trick works everytime for me. Until this time.

There’s a reason the city tourist maps are there. It’s official, standardized and well-designed. The information it provides can be considered of good source and selections. However, the DMO or a city tourism bureau is not the only entity that can benefit from a good tourist map. Restaurants, hostels, boutique shops, tour operators… see the perfect opportunities to get their business across to generous-spending tourists. Consequently, they commision private cartography organizations to come up with a well-designed map, good-to-know information and most importantly their brands on the spots that can’t be missed. These maps are then distributed among partners companies including accommodation providers. In a way, it’s useful and cost-free for independent tourists and backpackers who are the most likely and frequent user of tourist maps.

Like I said, whenever I’ve been, it’s the hostels that picked the tourist map I’d be using, be it the official ones from the DMO or the privately commissioned ones. It didn’t matter because they worked like wonders. In Verona, Milan, Venice, Rome, Nuremberg, Berlin, Riga, Cambodia… But this map that was handed out to me by the hostel in Prague didn’t.

There are three main problems with this map: its accuracy, transparency and ease of usage.

- Accuracy: this is somewhat a user heuristic. You have to physically be there to realize the map was misleading.

- Transparency: symbols without names, bus stops are hard to detect

- Ease of usage: attractions can not be traced directly from the map. Tourists need to remember the number of the site in question and turn the big bulky page to find the respective information in the subsections. To a backpacker with enough bags and stuffs on her hand (many times an umbrella in rainy days of April in Prague), this is totally an enduring and hassly practice.

However, the map does have some praiseworthy elements, namely tips for shopping, dining out and basic knowledge about history, cultures, etiquette… even simple vocabulary for tourists who want to be well-prepared. In this perspective, it is effectively a bite-sized travel guide handbook.

These few thoughts aroused my curiosity about tourist maps and after doing a bit of research around the field, it came to my appreciation that tourism cartography is as much a science and an art as cartography itself. A satisfying design of a tourist map should achieve the ultimate goal of ‘‘facilitate the correct reading and understanding’ (Zipf, 2002, p. 331). To reach that goal, the cartographers should consider some major elements of map design include marks, symbols, colours, contents, legends, scale, data and illustrations (Hong & Xie, 2010; Sarikanon & Sahachaisaeree, 2010). In the sphere of tourism, it is even more crucial that the cartographers get it right, as the tourists rely heavily on maps in a strange environment. Indeed, travel is a journey into the unknown and, accordingly, reading maps is an important activity for tourists at an unfamiliar destination (Brown, 2007). Not only can tourist maps be a self-guide for tourists to choose potential attractions and plan routes (Medynska-Gulij, 2003), they are also valuable marketing materials, as they ‘promote the identity of an area, as well as potentially increasing the local economic activity’ (Pritchard, 2008, p. 3). In brief, the tourist map, with satisfying design and contents, can be of dual benefits to both the tourists and the destination.

Making a good tourist map is anything but an easy job. Grant and Keller (1999) note that studies on design of travel maps should focus on factors including the following: scale, appropriateness of cartographic symbolism and text, effectiveness of graphic language, layout, inclusion of insets and photographs, depiction of transport and tourism infrastructure, illustration of parks and recreational areas. Among these, symbols and signs can be crucial to the readability of tourist maps. However, ironically, legends of maps used in the real world could be inefficient in ensuring ease and accuracy in relation to map reading (Clarke, 1989). Regarding the map contents, cartographers should pay attention to the level of details and the relevant information (depending on types of travelers and purpose of travel). For example, too much details can overwhelm tourists at first glance, which can be destructive to the primary purpose of facilitating tourists’ navigation while a tourist coming by car may not benefit from a map designed for backpackers who walk and use public transport. In its essence, tourism cartography is convincingly a hard job, which makes little surprise why not so many destinations have the willingness and resource to strike a successful cartographical product for tourism. Nevertheless, this should not discourage them from doing so, given the vitality of the tourist map to travel experience and the marketing of the destination.

In a case study of visitors satisfaction of Macao’s tourist maps, it is revealed that utility of map (understandable map signs, sufficient information on tourist sites, enough landmarks for wayfinding, covering all street names of interest, sufficient traffic information) wins over design elements such as color scheme, illustrations and scale (Yan & Lee, 2015). Similarly, Medynska Gulij’s study highlights two key functions of tourist maps, that is, facilitating choosing potential attractions and planning routes (2003). As long as the map is convenient for tourist use and is effective in helping them obtain information to choose tourist sites and plan routes, its mission is accomplished.

As far as Prague city map is concerned, although it has succeeded in providing insightful information about landmarks, history and culture, it has not yet provided the most basic information about tourist sites and street of interests nor presented them in an accurate and user-friendly way. My humble reccommendations are that:

- Its level of accuracy should be scrutinized and improved.

- Bus stops signs should be more informative and transparent.

- Rather than replacing landmark names with numbers and explaning them on the side, the map should lay out famous tourist sites by name on the map itself.

Reference list

Brown, B. (2007). Working the problems of tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 34(2), 364–383.

Clarke, L. M. (1989) An experimental investigation of the communicative efficiency of point symbols on tourist maps. The Cartographic Journal, 26(2), 105–110.

Grant, L. A., & Keller, C. P. (1999). Content and design of Canadian provincial travel maps. Cartographica: The International Journal for Geographic Information and Geovisualization, 36(1), 51–62.

Hong, Y., & Xie, X. (2010). The analysis of vision representation of the title and the character of illustrated map-sampled by sightseeing maps of villages and towns. Proceedings of 2010 International Conference on Design Theory and Practice, Taichung, Taiwan. (pp. 157–164).

Medynska-Gulij, B. (2003) The effect of cartographic content on tourist map users. Cartography, 32(2), 49–54.

Pritchard, K. (2008). Incorporating user opinion into a new wine tourism map for Southwest Virginia (Unpublished master’s thesis). Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, Virginia.

Sarikanon, C. and Sahachaisaeree, N. (2010). Graphical design features responding to tourist mapping need: A case of Bangkok’s maps for foreign tourists. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1226–1231.

Yan, L. and Lee, M. Y. (2014) Are tourists satisfied with the map at hand? Current issues in tourism, 18(11), 1048-1058.

Zipf, A. (2002). User-adaptive maps for location-based services (LBS) for tourism. Proceedings of the 9th International Conference for Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism, ENTER, Innsbruck, Austria. (pp. 329–338).

Leave a comment